Hi, and welcome to the third blog.

It is easy to play simple chords, beautifully in tune, in the middle register and higher using the harmonics of the horn. This can be done on any of the 16 tube lengths of the standard double horn. A few are only subtly different from their nearest neighbour and one is a quartertone different from the nearest neighbour. The longest tube length is a quartertone sharper than a long horn in B and is produced on the F horn with all valves pressed. However, it is quite difficult to produce a tone that is not stuffy. The shortest tube length is the B♭ horn. The usual setting of the valve slides then provides the descending chromatic scale, very closely tuned to match an equal tempered chromatic scale. These are shown at the end of this blog.

Harmonics 4, 5, 6 on each of the horn's tube lengths will usually give a very nicely tuned major triad. The tuning is even simpler to make true by playing the 5th harmonic slightly softer than harmonics 4 and 6. (Some horns are not as well focused on all tube lengths and some horns are not well focused on any tube length.) Good tuning by playing each harmonic with a well focused tone and no adjustment is possible on many well made horns.

The interval between harmonics 4 and 6 (ratio 6:4 & 3:2) is tiny bit wider than the same interval played on, say a nicely tuned keyboard. Harmonics give 702 cents, keyboard gives 700 cents. This is just enough to eliminate the 'beating' sound. (I can go into this more in a blog, otherwise I recommend the book Just Intonation Primer by David Doty for a clear explanation of the acoustical reasons for this.)

The interval between harmonics 4 and 5 (ratio 5:4) is quite a bit narrower than the same interval played on a standard keyboard with standard tuning, 14 cents narrower. The harmonics give a beautifully peaceful major 3rd without beats. The wider major 3rd might be considered more shimmering by some. However, the triad from the harmonics sounds strong and vibrant, especially when payed for longer than 1 second.

Here is a sound file of harmonics 4, 5, 6, (ratio 4:5:6) on all 16 tube lengths starting with the shortest.

The interval between harmonics 5 and 6 (ratio 6:5) is quite a bit wider than the same interval played on a standard keyboard with standard tuning. 16 cents wider, where the higher note is 316 cents above the lower note. This minor 3rd is the most vibrant just intonation minor 3rd, yet not the only good one. Interval ratio 32:27 is also good and very useful. It is easy to achieve: Go down a 5th from written C to F (ratio 4:3), down another 5th to B♭ (ratio 16:9), then another 5th to E♭ (ratio 32:27). Change the octave so the E♭ is higher than the original C. The higher note is 294 cents above the lower note, rather than 316 cents.

This can be useful in chord progressions. An example is the use of chord II in a major key.

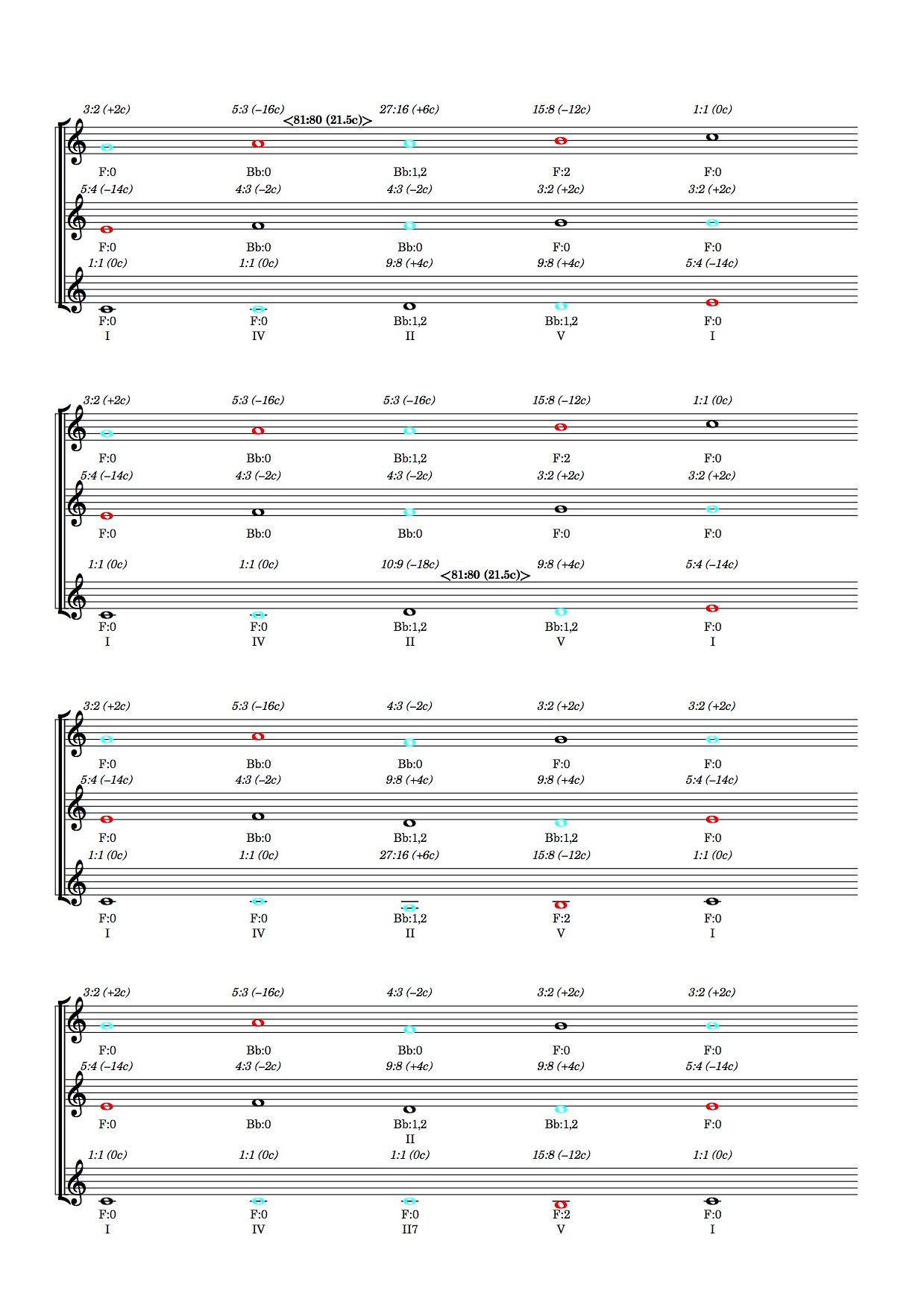

Here is a simple progression, in triads, of chord I - IV - II - V - I, played four times.

In the first example the 1st part moves between two written As: notes 2 & 3. The small pitch shift is the interval called a syntonic comma. The second example puts the comma into the low horn between notes 3 & 4. The third example avoided the comma shift by dropping all parts down a 3rd between notes 2 & 3. This does result in consecutive 5ths. The fourth example avoids those by making the 3rd chord a II7. A chord progression that avoids IV-II-V will not need any comma shifts, but maybe they are okay!

Here is a pic of the examples for easy study.

A later blog will give examples of 7th chords using 7th harmonics as well as the discordant 7th. Harmonics 8 & 7 together (ratio 8:7) sounds more like a barbershop quartet use of the 7th chord. Harmonics 9 & 8 together (ratio 9:8) gives a biting and exciting discordant sound, such as in Beethoven's Symphony 8, Mov. 1, bar 157 a II7 chord. Interestingly, two bars earlier the horns are also a tone apart (this time played on harmonics 10 & 9, though 1st horn best play a lightly sharper than the harmonic sits) in a diminished7 chord, which looks like a c minor chord in all other instruments except for 1st horn with the concert A. The whole tone can be a powerful sound.

The 16 tube lengths of the standard horn are:

B♭ horn, no valves

+Valve 2 = concert A

+Valve 1 = concert A♭

+Valves 1 & 2 = concert G, slightly sharp (+10 cents, or so)

+Valve 3 = concert G, slightly flat (-15 cents, or so, when set for the 2 & 3 combination)

+Valves 2 & 3 = concert G♭ (0 cents or +15 cents if the valve slide 3 is set for concert G)

+Valves 1 & 3 = concert F, quite sharp (+30 cents or so)

+Valves 1, 2 & 3 = concert E, quartertone sharp (+50 cents or so)

F horn = concert F, no deviation 0 cents

+Valve 2 = concert E

+Valve 1 = concert E♭

+Valves 1 & 2 = concert D, slightly sharp (+10 cents, or so)

+Valve 3 = concert D, slightly flat (-15 cents, or so, when set for the 2 & 3 combination)

+Valves 2 & 3 = concert D♭ (0 cents or +15 cents sharp if the valve slide 3 is set for concert D)

+Valves 1 & 3 = concert C, quite sharp (+30 cents or so)

+Valves 1, 2 & 3 = concert B, quartertone sharp (+50 cents or so)

The cent value is a useful measuring tool to quickly see relative intervals. A semitone has 100 cents and an octave has 1200.